A weight loss lesson from Little Red Riding Hood

I thought I had lost weight simply through diet and exercise, but a chance reminder of an old fairy tale gave me new insight.

Three years ago, about a month after my mother passed away, I woke up one morning and decided to stop eating anything with fur or feathers. The weight loss was quick, and I’ve kept it off ever since. The decision wasn’t based on a moral compunction to keep a sentient being from becoming dinner; at the time, it felt random, but I followed my gut instinct.

Not long after my mother died, while I was still taking care of my father in my apartment, I dismantled my parents’ two-story townhouse down to the last speck of dust. They had lovingly hoarded a lifetime worth of things. These things told an unspoken story and were rich with meaning, especially since they left Cuba decades prior with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

There was a method to their madness; the clutter was a clean, tidy repository of nostalgia, the warehouse of our family’s pain and the collective sense of loss expressed by Cuban exiles of my parents’ generation.

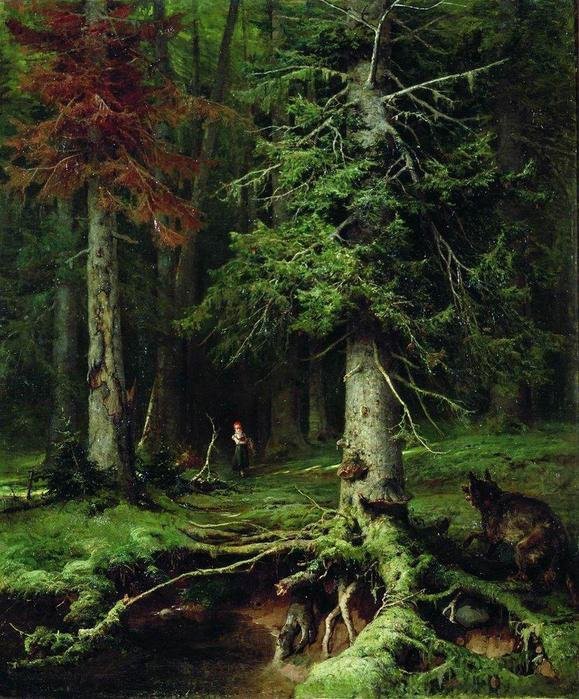

As I write, I’m on an open-ended road trip living out of one suitcase and last month, on the anniversary of my mother’s death, I climbed a mountain in the Adirondacks, 1,300 miles away from my hometown of Miami, to honor her life. When I descended, I felt particularly unburdened; the clean, crisp air and scents of pine and juniper invigorated my lungs.

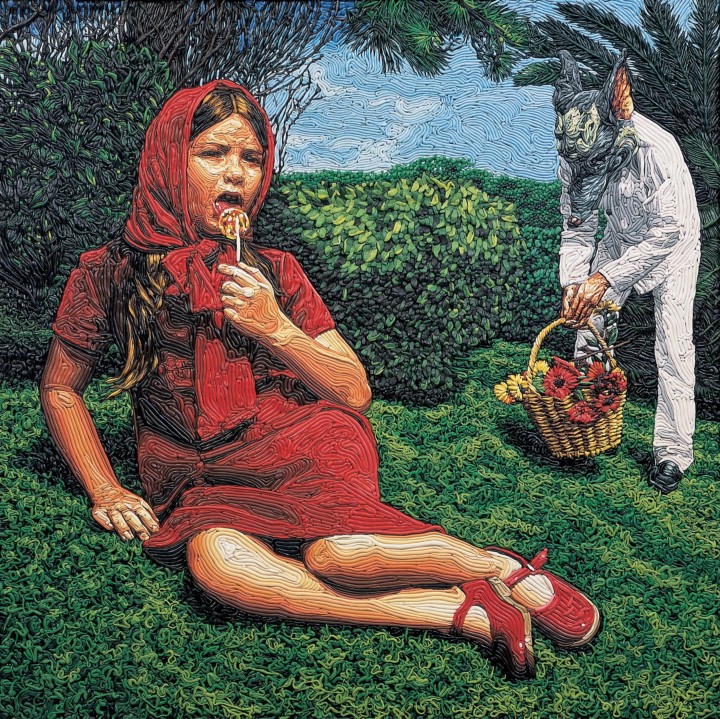

Later that same afternoon, I came across an image of Little Red Riding Hood on the cover of a children’s book and then it hit me: I lost the weight not only because of diet and exercise, but because I got rid of my parents’ clutter, my clutter — everything that no longer served me. I had been holding on to my parents’ pain — as well as mine — when I gained weight during my years as a caregiver.

Revisiting the story: weight loss and hunger

In one of the most popular versions of the fairy tale, Little Red Riding Hood disobeys her mother’s warning about avoiding the dangerous path as she wends her way to her grandmother’s house, carrying a basket full of food. When she strays into the forest, she comes across the wily wolf, who wants to devour her and the food in her basket. She naively tells him where she’s going and he gets there first, impersonating the girl in order to gain entry. The big bad wolf then eats the grandmother and hops into bed. When Little Red Riding Hood arrives, she mistakes the wolf for her grandmother, until disguised revealed, he eats our innocent protagonist. The end.

Another version has a happier ending. A hunter comes to the rescue, cuts open the sleeping wolf, and Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother emerge unharmed. The trio fill his belly with heavy stones while the he remains asleep. When he awakens he tries to flee, but the weight of the stones cause him to collapse and die.

But there’s more to this story than what goes into the belly’s wolf … read on.

The forest from the trees: weight loss and hoarding

Little Red Riding couldn’t see the forest from the trees and neither could I, until I climbed a mountain in the forests of upstate New York and beheld the infinity sky before me.

Back in Miami, when I dismantled my parent’s estate, the forest was dense with grief. I wouldn’t have learned this lesson that led to weight loss had I not endured the deep, dark and scary path of facing the big, bad wolf who represents the devouring nature of hoarding — the shift that occurs when the things we own begin to own us.

That’s what happens to the wolf: he’s unable to escape; he’s literally weighed down by heavy stones that prevent freedom of movement, stones that also bog down spirit, that build the walls of our own prison, that blind us to the things that really matter.

As my parents got older, I had suggested they move to a smaller apartment and let go of things they no longer even knew they owned, but this was impossible. Ultimately, the task came to me to cross the threshold and face the wolf, pack him up with all the burden of his pain and let him die, symbolically. The hunter, in my adaptation of the tale, is my own courage, which I didn’t even know I possessed, being weighed down and blinded by own fears.

It took about two weeks to clear my parents’ home, a whirlwind journey into the forest.

“My, what big things you have! My, how many things you have!”

But in all of that clutter, where where you, mami? I looked for you in the belly of the wolf, who lay in ambush, disguised as you, in the form of all your things, which were ready to swallow me up in grief.

Forgiveness in my basket led to weight loss

I eventually forgave my parents for their hoarding, although at the time, I resented them for the lesson. It had already been hard enough to see my mother die from Alzheimer’s while my bed-bound father was ailing from dementia.

I kept only the things that matter, and today I travel light through life, with no threat from any wolf, as I have very few things to lose. The wolf’s in my service now; he’s a great teacher.

Realizing the impermance of things and the illusory nature of the forest was my saving grace. With a lighter body, I have all the room for the one constant in my life: light and love and of course, infinite gratitude for what few material things I actually possess. These are always replaceable but nothing — no “thing” — can ever come close to the love I shared with my parents, which is really the only “thing” I carry in my heart.

The forest represents the heaviness of hoarding: its daunting, confusing and dark inertia, which leads to piles and piles of things that bury every fear that takes hold of us, clamps down on us with its gnashing teeth.

We put on the pounds and disconnect from our fears, but that makes us all the more tempting to the wolf. Being 80 pounds overweight, depressed and dying inside, was the dark, scary forest I needed to step into in order to travel through life unburdened by fear.

It doesn’t suprise me now that I lost weight so easily when I lost one parent, my mother, whom, of course carries huge symbolic weight for me as a woman encouraged to be brave, to be sure, but not without the “riding hood” of fear. I carried my mother’s fears within me; I was unconsciously cloaked in those fears. My weight and my blindness to the trees protected this pain.

What ultimately helped me lose weight, was to also forgive myself for the weight I carried. I could only fill that basket with love once I had emptied it completely, radically, once and for all, living happily ever after.

Little Red Riding Hood wasn’t carrying treats for her grandmother in that basket; she was carrying everything that no longer served her, which of course, could never really appease the voracious hunger of the wolf, who can never have enough of anything and dies from having too much of everything. The wolf suffers from the disease of more. I know better now: less really is more.

Today, I don’t carry things that don’t serve me. I don’t eat things that don’t nourish me. I see the forest from the trees and the food for what it is: a bounty for a thriving body.

— Originally published in Medium.