Fishhooks: A Caregiver’s Story

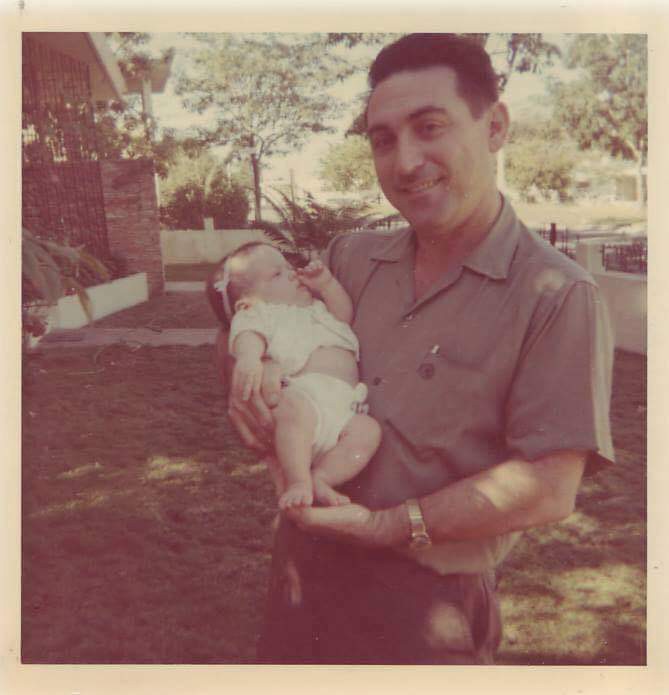

When I became a caregiver, visits to dad’s nursing home shored up childhood memories. Alzheimer’s robbed him of memory, but gave back love.

I felt so small, with nothing but a wooden bridge separating my little body from the roiling water flowing furiously out to sea, waves swooshing in a grey confluence of foam. The briny air filled my lungs. Slimy black ink oozed out of the squid daddy cut up for bait. Oh, this was no ordinary fishing adventure. No place here for the world of baby dolls and pretty pink dresses. Perched at the edge of something unknown, I sensed all would soon be different in the reverie of becoming a big girl.

I tugged at the line daddy handed to me, the other hand barely large enough to wrap around the edges of the yoyo. The current was too powerful, pulling me toward the scary rush of water. I couldn’t tell if a fish had bit or not and I clumsily jerked back from the rail, reeled in too quickly.

“Daddy, look!”

Oops. No fish, just a few drops of blood dripping down my leg where the barbed hook punctured my skin. Daddy gently tugged it out, mommy cleaned up the wound. I didn’t flinch. I kept fishing.

So that’s how it’s done. Reel in softly.

You are my son now, daddy, and I’m not always reeling in softly — I’m just reeling, helpless to take you from the nursing home where you’re dying, with nothing better to do other than stare at a blank wall, your muscles atrophying day by day as you lie in a small bed, swaddled in a diaper.

You told me many bedtime stories about the adventures of a little boy on the beaches of Cuba, but you never told me that decades later, after my first fishing trip, there’d be a fishhook stuck in my heart. You never told me I’d be embarking on a different adventure with you, returning to that little girl in a 40-something’s body, facing dark waters more daunting than those that flowed under a bridge in Biscayne Bay.

You are forgetful sometimes, but living in purgatory, unremembering what happened five minutes ago, is probably a blessing. How else to cope with the horror of your life? Buried alive as you are within the confines of a bed and a wall is a daily reminder of death. Sunshine comes only through the blindfolds of a window. You never recovered from a broken hip. You can’t stand up to see the canopy of an avocado tree draping over the drab roofs of Hialeah. You haven’t breathed fresh air in weeks.

Dispossessed of memories and simple human joys, the lost souls of this nursing home are God’s forsaken creatures. Five of you bide time in this living hell, trapped in tight quarters. I can barely fit a chair between your bed and the other patient’s, whose TV blares violent newscasts. The poor guy is practically deaf.

A fishhook still sticks even after I walk into the crowded room, your favorite mango milkshake in hand. The guy at the fruit stand around the corner always sends an hola. Your eyes light up and you cry, thanking God for the “miracle of you, my daughter.”

You still recognize me. Another miracle.

But it’s hardly relief. Your milkshake is cold, and so is my awakening.

The fishook pierces me deep, inflicting pain scarier than the torrent of waters under the many bridges we’ve crossed. I’m that little girl again. I feel so small. And this time, you’re not there to help me help you cross the final bridge.

But I still don’t flinch, daddy.

I can’t abide by human laws that are inhumane. What dark heart has written this mess of institutional elder care into practice?

You’d be proud of me, because I refuse to let anyone tell me that “he’s OK” while you stare at the outlines of nothingness, lost in the haze of limbo. I’m still not convinced that you’ve been properly diagnosed. I know in my heart that keeping you barely alive in this open coffin is not the way of love and I find myself shoring up the courage you instilled in me on my first fishing trip. To them, you are a medical case number. To me, you are my beloved father and I can’t bear to see you suffer.

I don’t blame those who care for you. Too many patients, not enough staff in the cash flow of Florida’s nursing home industry. I hate myself for not having planned to become a parent to you. I resent you for not having taught me to become a parent to you. I’m angry at the nation that worships vanity, lives in denial.

Music is our only solace, papi. We meet again at sea, holding hands.

That night on the bay, I didn’t even feel the fishhook, and later, we’d sing lullabies about fishes in saltwater, lyrics that carried me into peaceful slumber. These days, every time I visit, we sing the same lullaby, over and over, as if for the very first time. I pray that you’ll fall asleep before I leave, that you’ll not remember that I’ve just left five minutes later. I hold back tears when I step out onto the hot asphalt of the street, where chickens roam, cackling with callous indifference. The fishhook sinks deeper.

“The fishes want fresh water to drink, but there’s none of that here,” goes the refrain. Even as a child, I thought that the idea of fresh water in the sea was rather silly, but maybe that’s the message I needed to hear, incredibly, more than forty years after my first fishing trip. No, papi, there’s no agua dulce en el mar salado, but there’s plenty of love, even here, in fathoms of grief. And that is all I need to stay afloat. Watery memories soften the ache. The love you gave to me so abundantly, I now return to you in the ebbing tide.

— Originally published on Medium.